Several years ago, my wife and I went on vacation to Southern California and ended up with some of the worst food poisoning either of us has ever had. The beautiful California sun was shining just outside our hotel room, but we were too preoccupied with our sickness to care. A whole day was wasted because of one bad meal.

And we know exactly where the food poisoning came from. The only time we ate the same thing on that trip was the night before we both woke up sick; we had ordered pizza from a very famous food chain. I don’t want to say the name of the pizza franchise because I would hate to sully its good name, so for the purposes of this story, we’ll just call it “Patriarch Jack’s,” okay?

So we ordered a pizza from Patriarch Jack’s, and twelve hours later we were both doubled over in pain, praying either for relief or sweet death. Either would do, as far as we were concerned.

That was almost six years ago, and I still cannot eat pizza from Patriarch Jack’s. The thing is, I know I’m probably not likely to get sick again from that same pizza—if Patriarch Jack’s Pizza made everybody sick every time they ate it, the franchise would go out of business pretty quick. However, in spite of the logical understanding that Patriarch Jack’s is not likely to make me sick again, I probably won’t ever take a single bite of their pizza for as long as I live. I just can’t. My mind will always associate that brand of pizza with violent physical illness.

The emotion I’m describing here is called disgust.

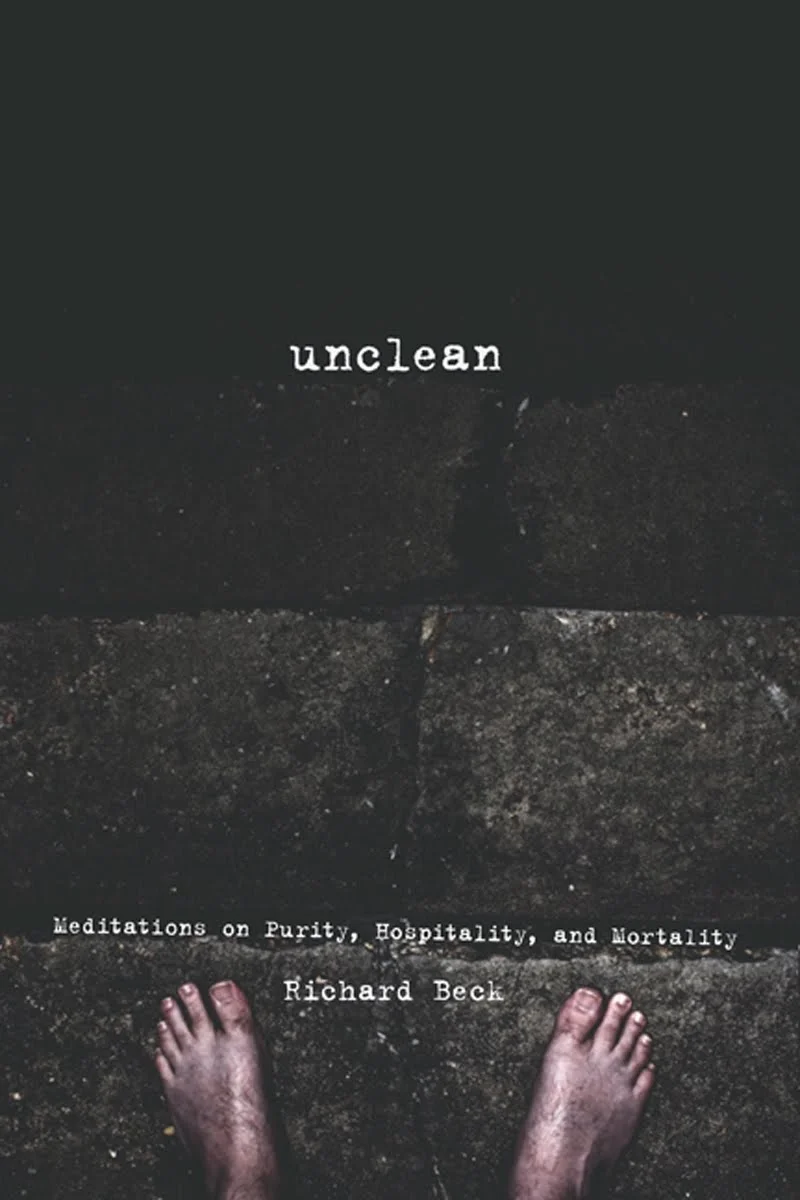

I recently read an excellent book about the spiritual dimensions of disgust. It’s called Unclean: Meditations on Purity, Hospitality, and Mortality, and it was written by the brilliant Richard Beck.

In the book, Beck talks about how disgust is a “boundary psychology.” That means that, in our desire to be clean or pure, we seek to keep certain things out because allowing them in would contaminate us in some way. So my feeling of disgust over my last encounter with Patriarch Jack’s Pizza has led to my ultimate conclusion that if I want to remain pure (read: not violently ill), I have to create a boundary between myself and Patriarch Jack’s Pizza.

Make sense?

Now here’s where things go from this being a conversation about physical health and safety toward being a conversation about how we view God and humanity. Let’s consider this question: What happens when my feelings of disgust aren’t about pizza—they are about other human beings?

During the time of Jesus, there was a group of people called the Pharisees who believed that the Roman Empire was oppressing them specifically because of people in their midst who lived “impure” lives. So the logical conclusion—as far as they could see—was the live such pure lives that God would rescue them from oppression. This purity came in the form of strict dietary laws, observing specific sacrifices at specific times of the day, week, or year, and any number of regulations regarding clothing, behavior, and participation in the Temple. The belief was that God would not rescue everybody, but only the people who had faithfully kept themselves pure, or “clean.” Everybody else was on their own.

So at some point, Jesus enters the conversation and begins to challenge this whole idea about cleanliness and purity. And he begins to interact with people who are perpetually “unclean,” including a tax collector named Matthew.

Tax collectors, it should be said, were the furthest from being seen as pure; they were local employees of the Roman Empire, enforcing Caesar’s tax laws and getting rich off of the financial oppression of their neighbors. Not only were they not participating in the purity rituals of the Pharisees, but they were moving in the opposite direction. Which is what makes this story about Jesus so fascinating and subversive-

As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. “Follow me,” he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him.

While Jesus was having dinner at Matthew’s house, many tax collectors and sinners came and ate with him and his disciples. When the Pharisees saw this, they asked his disciples, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?”

On hearing this, Jesus said, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” (Matthew 9:9-12)

So Jesus confronts the disgust-oriented theology in this group of people, and he says, “I desire mercy, not sacrifice.”

Here’s what Richard Beck says about this passage:

"This dynamic— purity via expulsion— goes to the heart of the problem in Matthew 9. The Pharisees attain their purity through an expulsive mechanism: expelling 'tax collectors and sinners' from the life of Israel. Jesus rejects this form of 'holiness.'Jesus, citing mercy as his rule, refuses to 'sacrifice' these people to become clean." (page 16)

“Sacrifice” means keeping other people out.

“Mercy” means letting other people in.

We still see this very tension all over the place.

When my parents divorced, the mother of one of my friends forbade her son from coming over to my house after school because of the sinful stain of divorce that marked our home. I was seven years old.

I once met an elderly woman who stayed far away from church for nearly fifty years because her father—a pastor—had so profoundly spiritually abused this woman to the point where she felt completely unloved and unwanted by God. Her great sin that warranted such condemnation? She smoked cigarettes.

I know a young lesbian couple who once were told not to return to a church small group because their presence made some people feel “uncomfortable.”

I could go on.

If you’ve spent any time in certain religious environments, it’s possible that you have encountered this type of mentality—a seeking after purity by keeping certain other people out.

(I should say that this is different than establishing healthy boundaries with people. That’s about maintaining your own health and well-being, not in being the moral police regarding other people’s lack of purity in your eyes. I plan to write more about health and boundaries in a future post.)

One of the loudest critiques I have received as a pastor is that my church practices something called Open Table Communion. That is, when we practice Communion, everyone who wants to participate is invited to do so. We have no membership requirements, and we don’t give people a theology quiz before they receive the bread and the wine.

Why?

Because I am not the gatekeeper. I am not the bouncer at the door of the club, holding the velvet rope closed for everyone except those who are most deserving of entry. That isn’t my job, and it isn’t your job, either.

Our job is to be a conduit of mercy, grace, and love toward those who are marginalized and pushed out. Our job is to remind people that Jesus insists that they already are clean, whether they know it or not.

Our job is to offer hospitality to the refugee.

Our job is to create safe space for people to encounter God and to heal.

Our job is mercy, not sacrifice.

Unless, of course, mercy is the real sacrifice.

Maybe our holiest moments happen when we look directly into the lives of others—especially those we are most likely to recoil against—and to see the image of God reflecting back at us.